Previous webpage: Maelstrom as the Flow Changes

“I was almost a sorry witness of such doings, knowing that a little theory and calculation would have saved him ninety per cent of his labor.”— Nikolai Tesla about Thomas Edison’s exhaustive experimentations.

Access and choices of news, entertainment, and information for the majority of the world’s population has shifted from relative scarcity to surplus, even overload. More than three billion people can now—via desktop, laptop, tablet, or smartphone—access more news, entertainment, and other information than had ever before in human history been printed or broadcast. The ranks of these of people will increase to nearly six billion by the end of this decade because all mobile phones now being manufactured are smartphone models capable of accessing this newfound cornucopia of content.

This epochal shift in readily accessible supply of news, entertainment, and information began four decades ago: no more than a wink in human history yet more than a generation ago in the lives of humans today. The shift occurred so quickly that young adults have not known anything but surplus, yet so slowly that older adults are only beginning to perceive the profound changes it has wrought. This cognitive gap, more difficult to bridge than a mere generation gap, today rends the media industries. The older adults who lead these industries or teach media too often use outdated theories, doctrines, and practices rooted in the waning era of scarcity; yet the younger adults who staff and the students who’ll soon join those industries haven’t yet enough lifetime experience and wisdom to fully formulate new theories, doctrines, and practices that comprehensively explain exactly how these industries must adapt to the dawning era of surplus.

Four decades into the epochal shift, the majority of executives and scholars still don’t understand how this change from scarcity to surplus is radically altering the media environment. Although some of them perceive scarcity’s dusk, but most seem myopic to the remarkable transformations in media theories, doctrines, business models, practices, and products that are dawning from surplus. They instead misperceive New Media merely as electronic distribution platforms the traditional media products, practices, and business models that were conceived in and based upon the scarcities of the Industrial Era: in other words, Mass Media. Failing to perceive and adapt to the epochal change underway, they are leading their industries into obsolescence. Their declining circulations or listenerships or viewerships once adjusted for population growth, and their fading market capitalizations and equity prices without adjustment, all attest their misperception and failure. Many major U.S. media corporations, in tacit admission of failure to adapt, have traditional products’ declining revenues once adjusted for inflation, their products’ been jettisoning their eldest and formerly most robust media sector products, the sector that first directly encountered the epochal switch: their newspapers subsidiaries.

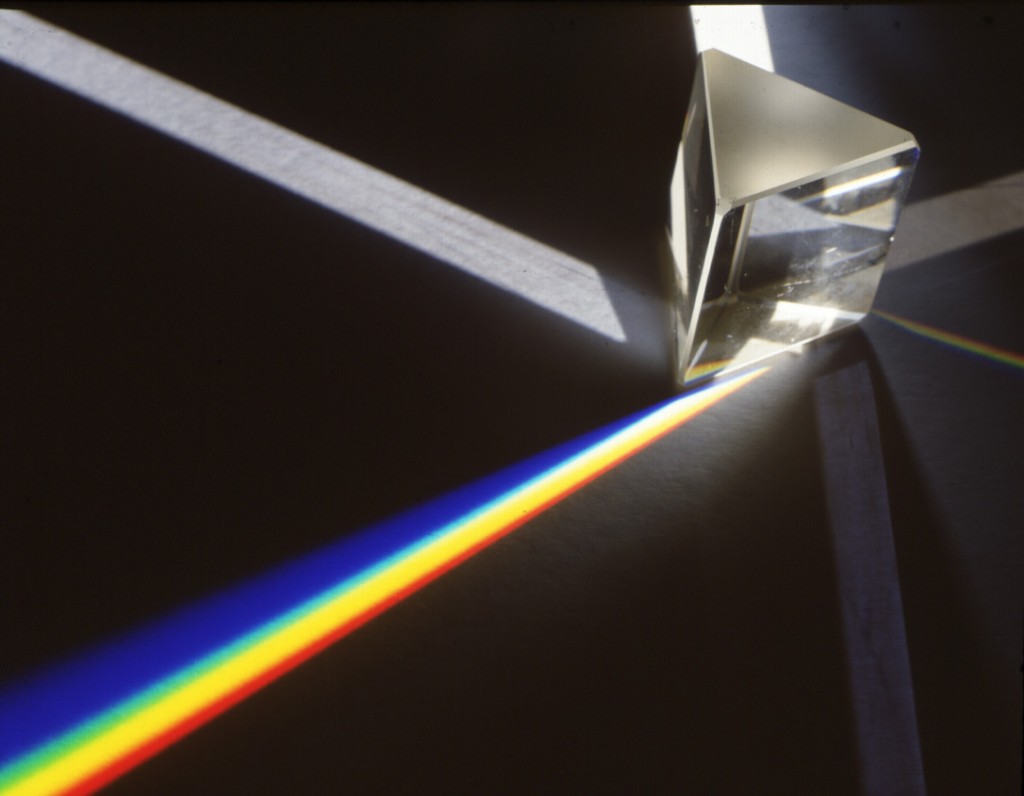

What you’re reading now is a primer about the epochal change underway in media, its many aspects, and what effects causes. This primer is condensed from the first month of the New Media Business postgraduate course that I’ve taught since 2007 at Syracuse University’s S. I. Newhouse School of Public Communications. It’s aimed at anyone who needs help perceiving the full spectrum of media change underway. In it:

- I’ll outline the basic spectrum of change underway in the media environment (including some aspects or ‘colors’ not easily or normally visible).

- I’ll delineate that spectrum into ‘color’ categories based upon whether aspects of that ‘color’ primarily affect consumer behavior, production and definition of content, or transaction and distribution of content.

- I’ll describe why the epochal switch from scarcity to surplus in people’s access and choices of news, entertainment, and other information, has made very many, if not most, of the Industrial Era theories, business models, practices, and products, all colloquially known as Mass Media communications, which have dominated media for centuries, increasingly unsuccessful, archaic, or obsolete.

- Likewise, I’ll specifically explain why a major effect of the changes underway is that general-interest Mass Media vehicles—such as newspapers, news magazines, and news broadcasts—are failing not only in their legacy forms but also when put online; and conversely why topical or ‘niche’ media in almost all forms are flourishing.

- Finally, I’ll explain why traditionalists in the media industries need to abandon their nigh alchemical search for a business model that will let their traditional Mass Media doctrines, practices, and products thrive fundamentally unchanged in this new environment. If traditional media companies want to survive, they must embark upon a radical overhaul of their doctrines, practices, business models, products, and industrial infrastructures. Their embarkation is already overdue.

The starting point for all of that is to look beyond the superficial of changes. Let’s start by slaying a pernicious misperception. Virtually all traditional media executives and traditional media academicians mistakenly think that the major change underway in the media environment is that people are switching their consumption habits from ‘analog’ to ‘digital’. These academicians and executives see fewer and fewer consumers reading printed periodicals or listening to over-the-air radio broadcasts or watching over-the-air or cable television video programming, and instead see more and more consumers reading, listening, or viewing news, entertainment, and other information via personal computers, electronic tablets, smartphones. The executives and academicians thus myopically assume that an ‘analog-to-digital’ switch is the greatest change underway; that the greatest, most important, or even most motive change underway in the media environment is that billions of consumers are becoming ‘wired’ or ‘hooked-up’ or going ‘digital first’. Similar misnomers are media ‘convergence’ or ‘multimedia’, terms which nowadays belie an Industrial Era perspective on media.

Although it is true that billions of consumers are now consuming media contents via computerized devices, that change is incidental. Those billions of consumers aren’t switching to use of computerized device because consuming media via computerized devices is easier. The devices’ screens are smaller than most television screens, harder to read than a book or magazine, more expensive and fragile than paper, and require a live connection to the Internet. Besides, most consumers in developed countries had already had books, newspapers, magazines, and radio and television receivers in their homes. Nor are those billions of consumers switching to computerized devices necessarily to obtain multimedia; the vast majority of the contents they consume on these devices is monomedia—a video clip, a song, or a webpage with or without still photos. Nor are those billions switching necessarily because computerized devices necessarily because these computerized devices can provide them with more up-to-date or information while mobile: the vast majority of contents they consumer on these devices is no more up-to-date than a daily newspaper or news broadcast and the majority of usage consumers make of these device is at home or in their office. Billions of consumers aren’t switching their media consumption to computerized devices for the sake of ‘digital’ or ‘wires’ or ‘wireless’ or being ‘digital first’. They are switching their media consumption for an even greater reason: because these devices provide them with so much more news, entertainment, and other information than all the paper ever printed and all the radio and television broadcast ever made can. They switch because New Media not only gives them much more news, entertainment, and other information than traditional media can, but commensurately let’s each of them find a better match of that media content to their own individual mix of needs, interests and tastes. The sheer appeal of that, fulfilled by every-increasing progress of New Media technologies, has fomented the greatest change in the history of media.

Unfortunately, those media executives and media academicians who instead misperceive some sort of ‘analog-to-digital’ switch or being ‘wired’ or ‘hooked-up’ or ‘digital first’ (or even ‘desktop to mobile’) as the greatest, most important, or even most active change underway in the media environment are blinkering, if not blinding themselves, to this greatest change and its panoramic spectrum of effects on the environment. Such simplistic and seductive misperceptions are the worst miscalculations a media executive or academician can make today. Those misperceptions lead them into the grave error of thinking that the New Media are merely ‘digital’ distribution mechanisms that have arisen for their traditional contents and products (i.e., ‘How can we put our newspaper online?’ ‘How can we use Pinterest as part of our broadcast?’ ‘How can we promote our magazine on Twitter?’). This myopia prevents them from seeing the New Media have reshaped the media environment in ways that are alien to traditional media theories, doctrines, practices, and produces; fields in which traditional media are themselves alien and unsuitable for transplantation. Executives and academicians who misperceive this way miss the truly major opportunities and changes underway in this new era.

The switch from ‘analog to digital’ (my catch-all term for all those misperceptions) is but a single hue in a far more colorful, powerful, and complex spectrum of change underway. The world’s media industries are woefully overdue to examine the complete spectrum, which is why most media industries have become, to use another trite term, ‘disrupted’.

Next webpage: The Prism & New Media Chromodynamics

Index of the Rise of Individuated Media webpages

© 2014