Among the approximately 1,350 daily newspaper titles published in the United States at the end of 1993 when I started working full-time in that industry’s online sector, slightly more than 100 of them had weekday circulations of more than 100,000 copies. According to data from PressGazette.com this year, nine do. During these past 29 years, the U.S. daily newspaper industry has lost two-thirds of its weekday and Sundays circulations; two thirds of its advertisers; and about 60 percent of its annual revenues.

Most of those losses have occurred since 2004, which not coincidentally is the year during which half of U.S. households and offices had gained broadband Internet access–‘always on’ access that didn’t monopolize those households’ and offices’ voice telephone lines to go online,

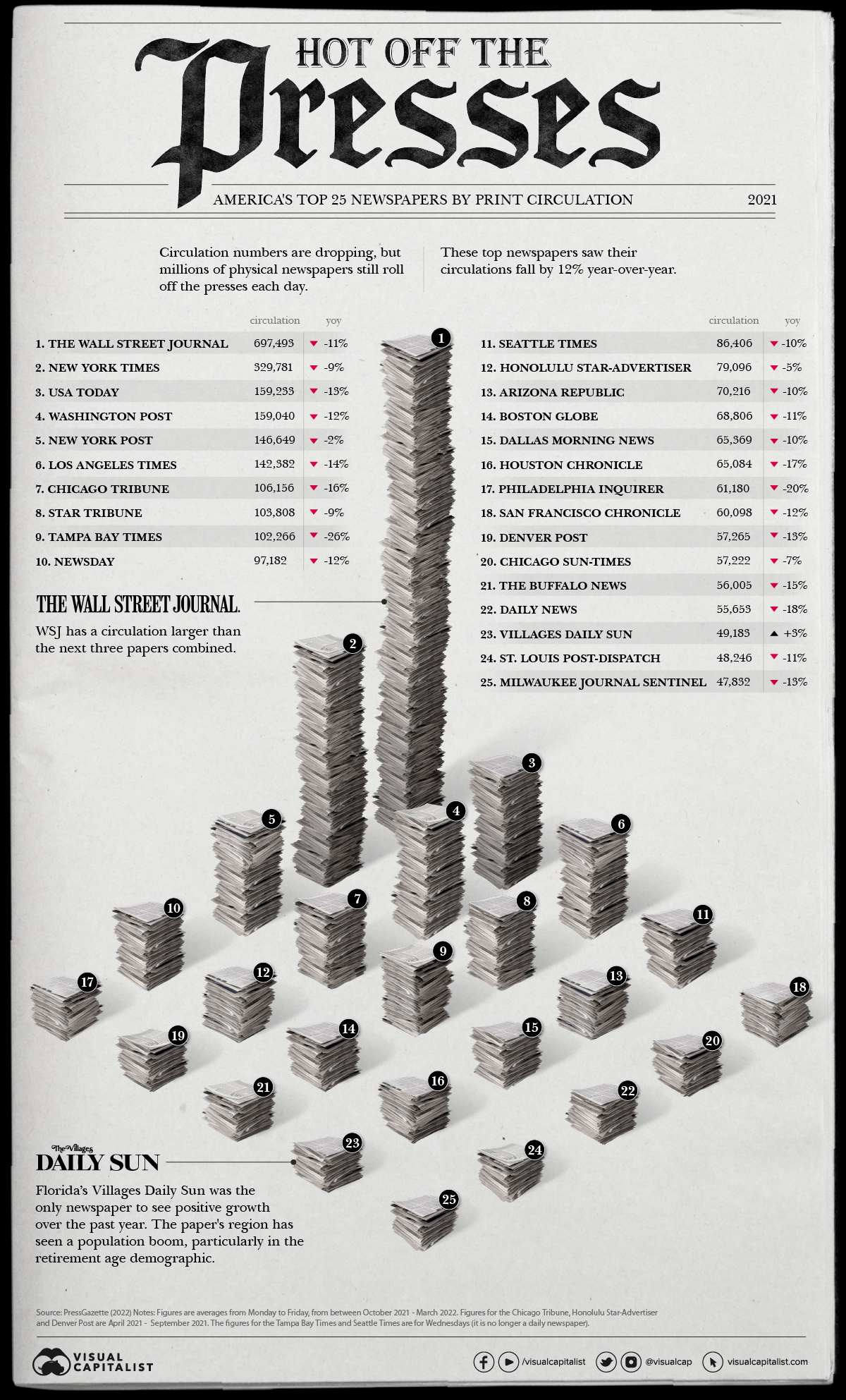

Although the circulation of The Wall Street Journal towers over that of all other U.S. newspapers in this graphic, it has lost some 35 percent since the beginning of the 2000s. Yet this newspaper is a business journal rather than a general-interest newspaper. Very many of its readers are reimbursed or given free subscriptions by their companies, an advantage which readers of most general-interest newspapers don’t have.

The circulation of The New York Times, slightly less than 329,000 copies per day, includes foreign copies of its international edition, and overall is quite a bit less than the 1.1 million circulation which daily newspaper enjoyed a dozen years ago.

Likewise, USAToday used to have more than a million circulation daily. However nearly three-quarters of that was ‘involuntary’: copies delivered by U.S. hotels under their guest’s doors throughout. Most of that ended during the recent pandemic, with just a bit less than 160,000 circulation remaining.

Yet USAToday isn’t the daily U.S. newspaper that has suffered the worst loss in circulation. That booby prize goes to the Daily News in New York City. Fifty years ago, it had 3.5 circulation daily. I has less than 66,000 now, a 98 percent loss.

Many U.S. newspaper industry executives might retort than none of these figures include ‘digital’ circulation: consumers who read the newspapers’ websites but who don’t purchase or subscribe to the newspaper in print. Don’t believe those executives. The ‘digital’ circulation figures they want to include are bogus for two reasons:

- First and foremost, their ‘digital’ circulation figures tally ‘monthly users’ of these daily newspapers. In other words, if someone visits a newspaper’s website only one time per month, that someone is counted as a ‘monthly user’ of a product that changes daily. Take the most advantageous example U.S. newspaper industry executives might user: The website of The New York Times. That newspaper’s public relations and advertising departments don’t agree on exactly how many ‘monthly users’ NYTimes.com has (the latter department characteristically tends to use a greater number). The numbers I’ve seen from these departments is either slightly more than 70 million or circa 100 million ‘monthly users’, which are certainly large numbers. However, a recent research study by four U.S. universities found that the average visitor to NYTimes.com visited it less than three times per month (equivalent to less than once every ten days). That would indicate a daily rate of 7 to 10 million user per day, although NYTimes.com releases no such daily figures. And though 7 to 10 million users per day might still be impressive for the nation’s largest general-interest newspaper, the median newspaper among the more than 1,200 remaining daily titles has around 10,000 weekday print circulation and welcomes about half as many ‘digital’ users per day: picayne online traffic.

- Second, not only does the median or average ‘digital’ user visit infrequently but does so quickly and shallowly during those few visits. The same four university’s recent research found that the visit spends an aggregate of fewer than five minutes on the newspapers’ website all month and sees fewer than three webpages per visit. That behavior is devastating to newspaper executives’ hopes that ‘digital’ use might compensate for their newspapers’ printed edition losses. Unlike with printed editions, in which each advertiser pays the newspaper a rate based the total number of people who subscribe and purchase copies, even if those consumers don’t even look at the printed edition that day, advertisers pay the newspaper only for the number of ‘digital’ users who actually did see the advertiser’s advertisement online that day. So, if the median or average ‘digital’ user visits only once every ten days, the newspaper can generate advertising revenue only that infrequently due to him. If when that ‘digital’ user does visit, if he sees only two webpages per visit, the newspaper generates advertising revenue from only those two webpages’ ads and not from any of the other advertisements on the websites’ other webpages; unlike the printed edition, in which the newspaper generates advertising revenue from all the advertisers who’ve placed advertisements in that edition’s pages. The overall results is that ‘digital’ editions generate far less revenue than printed editions do.

The U.S. newspaper industry thus is obviously dying. How long will it last if it continues to suffer 12 percent annual losses in its printed editions’ users?