Perhaps I’m the only dissident among the approximately 250 media scholar attending the World Media Economics and Management Conference held this week in Cape Town, South Africa? The chosen theme of the conference is ‘In the Age of Tech Giants: Collaboration or Co-opetition?’

Their specifics:

“The intervention in the market of global technological giants such as Google, Facebook and Apple – the so-called Big Three – and others has deepened and accelerated traditional media’s existential financial and economic crisis, which was also exacerbated by the worldwide economic downturn of 2007-2009. “In recent years, several leading media firms around the world have willingly handed over their content to Facebook’s ‘Instant Articles’, Apple’s News, and Google’s Mobile Pages to seek what has been promised as great and faster distribution of their content to audience and increased revenue.”

It’s temporally an apt theme. However, I dissent from my academic colleagues because the conference theme (whose author I know and respect) nonetheless fails to see the overall shift underway in the media environment. My colleagues, most of whose lives have been about the study of Mass Media, are blinkered by those manifestations of Industrial Era technologies that are indeed colloquially known as Mass Media.

My turn to be specific:

During the past 25 to 45 years (the exact duration depending upon in which country you live) the greatest shift in media history has occurred. That is the shift from relative scarcity to surplus, even overload, in people’s access and choices in news, entertainment, and other information. More than half of the world’s 7.8 billion people today own computerized devices through which they can obtain more information than has ever before been printed or broadcast. This change in the media environment has effected more people more quickly than either the inventions of the printing press or the broadcast transmitter.

It has fundamentally changed how half the world’s people consume news, entertainment, and other information. Almost all of those 7.8 billion people each now take advantage of their newfound cornucopia of content to find a better mix of items that match his own uniquely individual mix of needs, interest, and tastes, than he can get from any Mass Media vehicle (such as a periodical or a broadcast channel, etc.)

For example, according to usage survey firms such as Nielsen, the average American visits up to 100 different websites (social media, blogs, traditional media websites, etc.) per month, regularly visiting approximately 24 during that time. Only ten to 20 of those website per month are those of traditional media. Almost none of these people had subscribed or otherwise regularly consumed 24 periodicals or broadcast channel — nonetheless 100 — prior to the opening of the Internet to the public. However, they don’t thoroughly consume any of these ten or 20 or 100 websites. They generally see only one or two stories (or items) on each website per visit. Nobody reads an entire website they way they once at least glanced at each page of the printed daily newspaper they used to read. In other words, half the world’s people now consume more media than ever before, from far more sources, but they consume each source’s or vendor’s website much less thoroughly, much less often, than they did with what’s now called ‘legacy’ or ‘traditional’ media (i.e., broadcasts and printed periodicals).

The result is that as they switch their consumption from ‘legacy’ or ‘traditional’ to online, they use those vendors, as well as those vendor’s ‘legacy’ or ‘traditional’ packages of content much less frequently and much less thoroughly. Data, which used to be publicly released by companies such as Nielsen or ComScore but which now is no longer at the embarrassed requests of ‘legacy’ or ‘traditional’ media companies, confirms this.

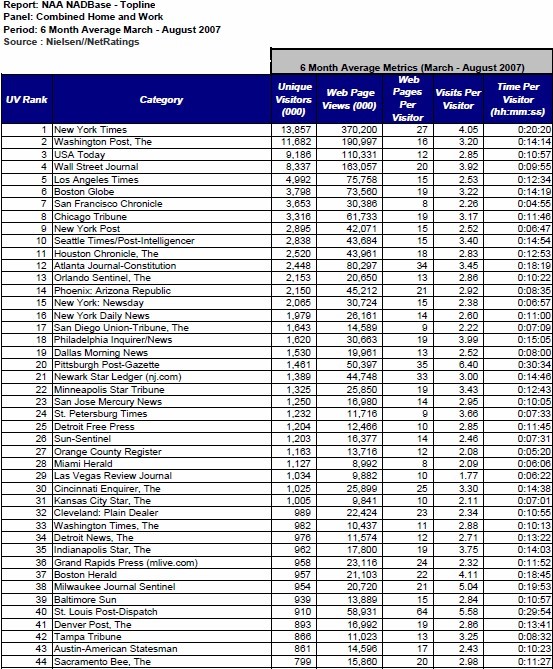

For instance, the table below showed how often, and how much, U.S. major daily newspapers were used by the newspapers’ average online user. Scholars of Mass Media and practitioners of Mass Media will focus on the ‘Unique Visitors’ and ‘Web Page Views’ columns because readership and circulation are traditional metrics of Mass Media. At the time of this chart, The New York Times’ website had nearly 14 million users per month and displayed more than 320 million page views during the month, which sounds great to Mass Media people (The New York Times then had only 1.5 million readers in print).

Yet anyone attuned to New Media will immediately focus on the chart’s ‘Web Page Views’, ‘Visits per Visitor’, and ‘Time per Visitor’ columns, each of which shows how consumption has shifted. The average user of The New York Times’ website visited it only 4.05 times per month – which is almost exactly only once per week; sees only 27 web pages (i.e., stories per month) – which is only six webpages per visit per week; and spends less than 20 minutes and 20 seconds on the website all month – approximately the same amount of time it might takes to read The New York Times printed edition per day. Those are abysmal Mass Media statistics for a daily-changing publication, particularly the for the premiere daily newspaper in the United States. And the data for lesser U.S. newspapers are almost all even worse. It’s clear that people online consumer daily newspapers much differently than they consumer that some content in print.

This Nielsen table dates from 2007. The New York Times’ website today has nearly 80 million monthly users, growth that reflects the worldwide growth of online usage. However, the ‘Web Page Views’, ‘Visits per Visitor’, and ‘Time per Visitor’ nowadays are approximately the same as then. The ‘NAA’ in the table’s title is the abbreviation for the Newspaper Association of America which no longer publicly releases such data.

The forms of ‘legacy’ or ‘traditional’ media colloquially known as Mass Media have a fundamental disadvantage in the new media environment (or I could likewise, although not so accurately, say ‘the New Media’ environment’). The methods by which Mass Media companies produce, package, distribute, and sell their contents are actually artifacts of the hallmark limitation of Industrial Era media technologies. (What are colloquially termed ‘Mass Media’ are indeed Industrial Era products.) The hallmark limitation of those technologies – the analog printing presses and the analog broadcast transmitters — is that each consumer of a Mass Media product (such as a newspaper or a magazine printed edition or an over-the-air or cable or satellite television or radio broadcast) sees the same content simultaneously as every other consumer of that product. Analog presses or analog broadcast transmitters are incapable of producing a unique edition or broadcast for each consumer based upon that consumer’s uniquely individual mix of needs, interests, and tastes. As a result during the Industrial Era, a print editor or broadcast producer would select what stories or entertainments to package, based upon what stories or entertainments he though have (a) the most widespread demographic interest or (b) he thinks he should bring to the attention of of his product’s consumers. Hence, the traditional newspaper edition or general (or even topical) magazine edition or broadcast news broadcast or broadcast entertainment program schedule.

Whatever mix of stories or entertainments an editor or a producer chooses for his Mass Media product, it will never be an exact match for each and every one of his product’s consumers. Each person is a unique mix of a few general interests, some group interests, and very many largely individual interests. It’s this unique mix that makes us individuals.

A teaching exercise I use with my graduate students or in executive education is to ask them to name what interests each and every person in a community. Except for the weather, there are precious few such topics; even newspaper editors can’t name many. Most children and teenagers aren’t interests in taxes or politics or the economy, nor are interesting to many adults. Many people do share group interest: fans of Manchester United or Italian cuisine or Prada handbags, etc. Yet everyone has their own individual specific interests, such as someone who is interested in bonsai gardening, the acting of Alicia Vikander, beef rendang, Euro-Disney, reggaetón, etc., even if that person might know few or no other people who share one or more of those specific interests. It is the unique mix of a few general interests, some group interests, and many specific interests, is what makes us each individual. It’s what individuates us.

Given their newfound cornucopia of content, almost everyone naturally tries to find a mix of content that best matches their own unique mix of individual interests and they use Mass Media mixes less. It’s behavior similar to that of people who’ve always been given a standard meal (such as an institutional meal consisting of items chosen by a cook or nutritionist) but are now given the ability to choose whatever they want from a gargantuan buffet – each person will self-select their own choice of items, perhaps each person obtaining a different mix of items, rather than continue to consume the same standard meal as everyone else had.

The means by which half the world’s people have begun to find a better mix of items than Mass Media products gave them began with the rise of online search engines during the 1990s. Millions of people began to using those to self-individuate the mix they obtained. Once collaborative filtering/social media applications were developed that create individuated ‘news feeds’, billions began using those to obtain an individuated mix of contents. More recently, even more articulately Individuated Media applications (such Spotify, Flipboard, etc.) have attracted hundreds of millions of users. Individuated Media are superseding Mass Media as the predominant means by which most people obtain news, entertainment, and other information. That has already happened for most adults under age 45 in developed countries.

Is Facebook a Mass Media company? With two billion users, it certainly has mass reach; yet each user simultaneously sees a different (individuated) mix of contents than any other user does, unlike with Mass Media. It’s an Individuated Media company. The hallmark limitation of Industrial Era media technologies — that each consumer of a Mass Media product must see the same content simultaneously as every other consumer of that product – doesn’t apply to Google, Facebook, Twitter, Spotify, Flipboard, Sina Weibo, Pandora, Vkontakte, Twitter, ,etc. Those are Individuated Media companies. Search engines, collaborative filtering applications, social media, and other companies that allow a person to individuate what mix of news, entertainment, and other information a person receives, as all Individuated Media companies.

Some of these companies are, for lack of any other adjective, lucky. Search engines arose because the sheer volume of contents online became impossible to search without them. Facebook was initially just an online version of the printed ‘facebook’ of incoming students at Harvard University. That printed facebook featured each of those students’ photo plus a list of a few interests of each of those students. Mark Zuckerberg and his company simply shoveled that model into put online, creating hyperlinks between those interests. What he and his company didn’t realize at the time was they were tapping into the desire of people (initially Harvard students) to find friends or others with interests like their own. The explosive growth of Facebook, first at Harvard, then at other universities, and then in the public at large, resulted. Facebook initially wasn’t intending to become a major media company or to dominate the content individuation market. Facebook luckily tapped into that. Their current domination as an Individuated Media application was somewhat fortuitous and accidental.

Academicians or media executives who expect the production, packaging, distribution, and business models of Mass Media to continue in competition with Individuated Media are in the dark. The production, packaging, distribution, and business models of Mass Media, as well as very many Mass Media theories, doctrines, and practices, all of which arose during the Industrial Era (a period I date as starting with the invention of Gutenberg’s moveable-type analog printing press in 1459 – the first mass production machine — rather than the invention of steam powered factories centuries later) have become obsolete and are being replaced by the theories, doctrines, production, packaging, distribution, practices, and business models of Individuated Media.

The Industrial Era products known collectively as Mass Media become replaced by the Informational Era products known collectively as Individuated Media. Questions of how to how to apply Mass Media in Individuated Media don’t make sense. The apt questions are how should or can Mass Media companies and their products adapt to the new media. Most will fail. Many already have or are failing.

Media conferences should (indeed, must) instead focus upon how to media companies, whether ‘legacy’ or ‘traditional’ or ‘pure-play Internet’ or ‘New Media’ can produce content and obtain renumeration for that in Individuated Media. In other words, within the new media environment. That’ a conference I’d like to attend, manage, or produce.

#